graphene: All global and European innovation rankings present Poland as an outsider. We are already so used to this gray image that with the recent publication of the results of the EU innovation ranking, the media triumphantly announced: “Poland in fourth place from the end”. And yet we have great scientists, and we do not lack young talents. What is missing is something that should be found between research and its commercialization.

Research conducted last year at the request of the National Center for Research and Development showed that as many as 41% of Polish scientists do not undertake activities related to the commercialization of their research. Why? In the opinion of over 53% of respondents who do not conduct commercialization activities, one of the most serious barriers in this process is the lack of competencies needed to acquire a business partner.

41% of Polish scientists do not undertake activities related to the commercialization of their research.

What does it mean? Are scientists speaking a different language than entrepreneurs? Perhaps the answer to this question can be found in another NCBiR study, also from last year, which showed that the reluctance of researchers to leave laboratories and to introduce their solutions to the market results from fear of the risk of failure and underestimation of their intellectual property. These concerns may be justified as the market is ruthless and customers immediately eliminate unnecessary and uninteresting products. Where the customer decides, the consequences of a mistake can be dire.

We have really great scientists whose achievements amaze the world, but we are unable to monetize their research for various reasons.

On the other hand, the environment of investors and entrepreneurs emphasizes the lack of efficient cooperation between public institutions and the business environment in creating solutions conducive to commercialization. Potential investors also lack extensive information on research projects underway that have the potential to create a commercial product, technology, or service. And precise information is an essential element to start the process of commercialization of research results. Scientists’ closely guarded secrets mean that knowing who is working on what and at what stage of research is practically available only in the final stage or when patent applications are submitted. Entrepreneurs learn about them in a formal and informal way – at conferences and scientific symposiums organized by universities, through technology transfer centers, or through business environment institutions, such as foundations, consulting companies, or research funding institutions, such as NCBiR and PARP.

The lack of efficient and, above all, ongoing communication between scientists and investors means that entrepreneurs show far-reaching concerns about investment risk (77% of respondents) and the time-consuming nature of processes (48%). The mutual trust of the participants in the process, which is the basis of every joint action, did not do well in the study. Investors complained about difficulties in building an understanding with scientists. It is about basic interpersonal contacts and the general state of social trust, and the existing stereotypes. In investor-scientist relations, there is an opinion that the investor is a predatory capitalist who dreams of nothing else but taking advantage of a poor scientist. The study made it clear that scientists are most concerned about stealing an idea, using it, and losing control. The fears are not entirely unfounded, as there are cases of funds on the market that unscrupulously used the ideas of scientists and made millions for themselves, without sharing the profit fairly with the developers of the solutions. But there are also funds that grow along with subsidized innovators. Perhaps, due to fears of a dishonest partner, scientists with a flair for business launch enterprises themselves to introduce their discoveries to the market, solutions, or ideas. But without professional support and investment, it is often difficult for them to successfully enter the market.

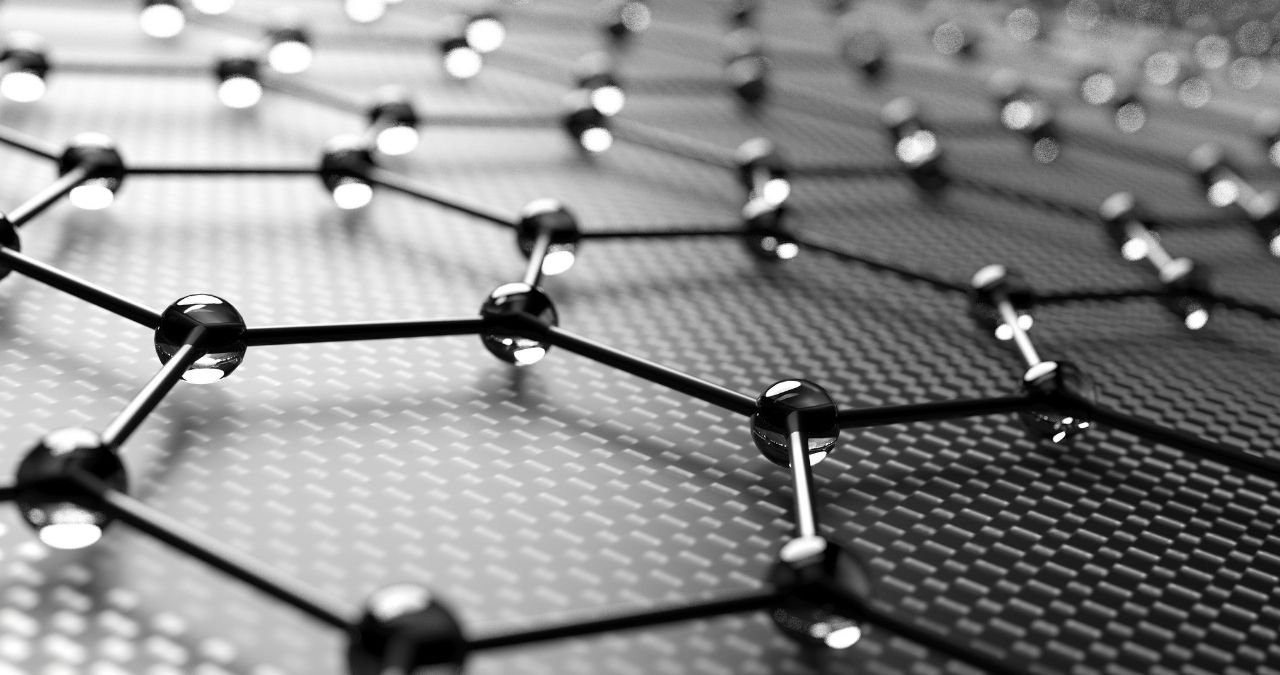

From time to time, however, it happens that a breakthrough invention appears in Poland that may change the rules of the game on the market. Then, as in the case of Polish graphene, sensation-hungry media trumpets left and right about the success of Polish scientists. The discovery of graphene, a honeycomb form of carbon just one atom thick, was initially only exciting for scientists. But when it turned out that it is a great heat conductor, flexible and very durable, and thus an excellent substrate for electronic systems and components, there was a vision of processors made of graphene, which, thanks to better conductivity, would be many times faster than solutions based on silicon. The technology race has begun around the world to see who can develop cheap production technology the fastest and win incredible profits. And here the Polish thread appeared – in 2010, a team from the Institute of Electronic Materials Technology (ITME) led by Dr. Włodzimierz Strupiński patented a cheap method of producing high-quality layered graphene. When the media publicized the case, the world first heard about “Polish graphene.” Money was found for subsidies, and work on the commercialization of research began. Five years later, the subsidies ended, and there were no investors willing to spend really large sums for further research. Work slowed down, and while technologies emerged, it was too early to develop ready-made products with which to go to the market. When politicians took up the topic, “Polish graphene” found itself in agony. With which you could enter the market. When politicians took up the topic, “Polish graphene” found itself in agony. With which you could enter the market. When politicians took up the topic, “Polish graphene” found itself in agony.

The graphene example is not alone. We have great scientists whose achievements amaze the world, but we are unable to monetize their research for various reasons. Hope in the youngest generations, who grew up in Poland belonging to the European Union and without any complexes, look for their chances not only in the country, boldly competing with their foreign peers. The problem is that these young and often outstanding talents need help in gaining knowledge and conducting research. And not everyone wants to give it. This is shown, for example, by the stories of two young scientists, Ola Snuzik, who conducts research on the healing properties of onion extract, and Igor Kaczmarczyk, who studies the bactericidal properties of amber, presented on the following pages. In addition to talent, they were also very lucky because they found wonderful teachers and scientists who helped them develop their talent. However, they do not have much chance in Poland to conduct more advanced research and further broaden their knowledge.

Also Read : Moving a Company, What Is Worth Remembering?